Tefnut's Environmental and Drought News Article

By Alexis Madrigal January 7, 2010 | 2:00 pm | Categories: Energy, Environment, Health

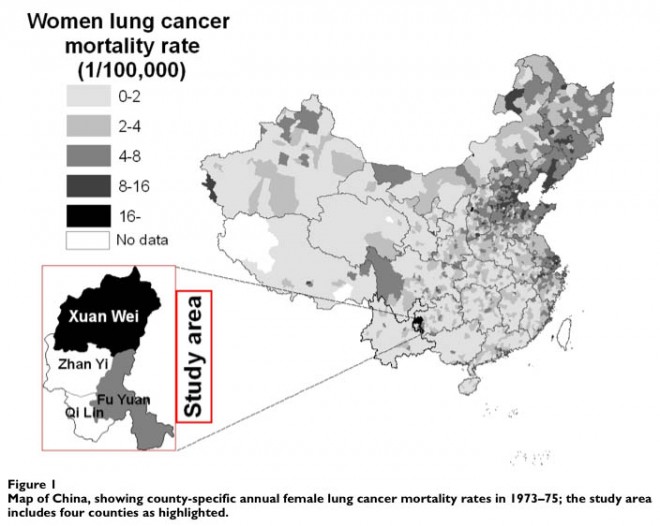

A seam of coal formed 250 million years ago during the worst extinction event on record appears to be responsible for the anomalously high lung cancer death rates among women in the rural Chinese county of Xuan Wei in Yunnan Province.

It's long been known that the lung cancer mortality rates in the region were the worst in the world among female nonsmokers and some anomaly in the coal had been suspected. Lung cancer mortality in the region is up to 20 times the Chinese average. But it's only in recent years that scientists have focused in on silica in the form of very fine quartz as the mineral that makes burning the stuff so deadly.

Now, in a paper published in December in Environmental Science and Technology, Chinese, British and American researchers have proposed a link between the silica in the coal and the massive event that nearly wiped out life at the Permian-Triassic boundary.

"What we're saying is that the geologic and climatic events that nearly extinguished life 250 million years ago is still having an impact because its imprint is in the coals that the people are using," said Bob Finkelman, a geologist at the University of Texas, Dallas. "They are inhaling this material with nanoquartz that was precipitated 250 million years ago and in a sense it's extinguishing life in the community."

Throughout the early 20th century, the inefficient combustion of soft, bituminous coals smoked up the emerging industrial cities of the world. Similar problems now plague the developing world, both in cities and the hinterlands, where the coal is often used for heating and cooking. The inhalation of the particulates, trace minerals and other substances contained in smoke can lead to a variety of health complications: The World Health Organization estimates that 1.6 million people die each year as a result of indoor air pollution.

The new study underscores the variability between coals in the world. Some coals are particularly smoky, sooty or otherwise undesirable, while others burn cleaner. Coals formed at different times in the earth's history, so even though the dominant component is carbon, each seam has a very particular chemistry.

"Even when you look at coal from a small region, there's enough variation in the properties that you can't just call it all coal and expect it to have the same health effects when you burn it," said Donald Lucas, a physical chemist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. Lucas co-authored a paper on the nanoquartz in Xuan Wei's coal with geologist Linwei Tian of Chinese University of Hong Kong who did pioneering work on the subject.

What Finkelman's work provides is a plausible account of why this particular coal may be enriched with silica. While there are several hypotheses for what caused the mass die-off at the Permian-Triassic boundary 250 million years ago, a major volcanic episode is likely to have contributed to the phenomenon. Massive amounts of gases leaving Siberian basalts are believed to have radically altered the geochemistry of the atmosphere.

"It lead to highly acidic rain which denuded life on the surface of the earth and acidified the rivers and the oceans," Finkelman explained. "It was so intense that they believe it actually dissolved a lot of the rocks on the surface, mobilizing the silica."

That silica was carried by groundwater into peat that over geological time became the coal the Chinese residents in the region use as a fuel source for cooking. Coal from this time period is not known to be used for indoor cooking elsewhere.

In Xuan Wei, the direct combustion of coal for cooking has waned in recent years, but basic cookstoves, sometimes without ventilation, have long been employed. Epidemiological studies as far back as 1991 found that the more time you spent cooking, the more likely you were to get lung cancer (.pdf).

Now, residents have been getting better stoves or moving into apartments, where they have electricity, Finkelman said, but the local coal still presents a problem for thousands.

Public health biologist Joseph Bunnell of the U.S. Geological Survey, who was not involved with the work, said the next step will be to try to determine exactly how the tiny silica particles could combine with other carcinogens in coal smoke to be so deadly.

"What needs to be done from an epidemiological point of view is to establish biological plausibility," Bunnell said.

Image: 1) Pushing coal in Sichuan Province/AP. 2) BMC Public Health.

Citation: "Silica−Volatile Interaction and the Geological Cause of the Xuan Wei Lung Cancer Epidemic" by David J. Large, Shona Kelly, Baruch Spiro, Linwei Tian, Longyi Shao, Robert Finkelman, Mingquan Zhang, Chris Somerfield, Steve Plint, Yasmin Ali, and Yiping Zhou

WiSci 2.0: Alexis Madrigal's Twitter, Google Reader feed, and green tech history research site; Wired Science on Twitter and Facebook.

Source: Wired

© 2010-2026 Bill McNulty All Rights Reserved