Tefnut's Environmental and Drought News Article

The Water Industry Must Take on the World

By Nick Butler and Ian Pearson

August 17, 2011 10:44 pm

The $2.4bn bid for Northumberland Water by a fund owned by Hong Kong industrialist Li Ka-Shing last month was seen as just the latest takeover of a British utility by international investors. In reality, it is the latest in a series of early moves that may yet reshape the global water sector. Yet in the coming era of water shortages and water conflicts, there is urgent need for greater global integration in an industry that, for historical and political reasons, remains overly national both in scope and ambition.

A global population expanding by 220,000 people a day requires new sources of water. To be fair, corporate activity in this area is increasing. In Israel, Whitewater, a leading water technology business, is completing a new funding round to support international expansion. In Singapore, KKR is reported to have paid $114m for a stake in a wastewater treatment company to gain access to the Chinese market. Despite this, however, few water companies operate outside a confined geographical area. Just as the energy and electricity sectors have become international, so now we need to see the emergence of truly global water multinationals. The reluctance of water companies to venture into international markets is rooted in history, and a handful of bad experiences. Water industry investors have seen the sector as a utility play – dull, but safe from cyclical pressures and volatility.

This is a particular opportunity for the UK, where the water industry is arguably the most successful of all the 1980s privatisations. British water companies have, with few exceptions, provided reliable supplies for their customers and have improved environmental conditions. Glass Cymru, the Welsh water company, has even been transformed by creative management into a business in which its customers are its owners.

Despite a tough regulatory regime, these companies have retained the confidence of investors to the extent that to Mr Li and others, they now seem undervalued.

Their full potential has not been realised, however. British water companies, along with a few others across Europe, have the technical and managerial ability to take on the challenges of global water. They could develop supplies to the new cities of China and India, as well as playing a major part in Africa. They could also improve environmental standards to make water clean and safe. So far, they have not done so.

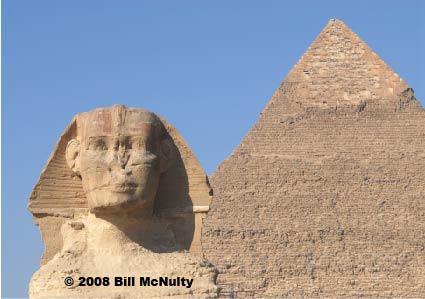

This is a shame, because the global water challenge will not be solved without imaginative corporate expansion. Global consumption of fresh water is rising by more than 60,000bn litres a year, yet more than 1bn people are without a safe supply. This is compounded by issues such as the unsustainable exploitation of fresh water and desertification – where the Sahara advances south by more than 40km a year.

Water is central to the development plans of the fastest growing economies of Asia, the Middle East and Latin America. Across the world water needs to be found, conserved, managed, cleaned and delivered.

Where no alternatives are available, desalination must be developed and deployed. Water needs to be protected from the dangers of disease and the threat of global terrorism. The skills to manage water are therefore of huge value, providing they can be improved and expanded.

Of course there are risks. But domestic consumers can be protected by ringfencing different activities, and international ventures can be structured to attract those prepared to take more risk. Clear regulation can protect the principle of providing a good-quality service at home, while allowing the collaboration and partnership that will be needed to secure global markets.

Water can be one of the great industries of the 21st century. The early transactions and takeovers now under way should mark not just the transfer of utilities from one owner to another, but the creation of an entirely new global sector, capable in time of matching energy and communications in importance and value. Water companies should seize the opportunity.

Nick Butler chairs the Kings Policy Institute at Kings College London. Ian Pearson is a strategy consultant and former UK government minister

Source: Financial Times

© 2010-2026 Bill McNulty All Rights Reserved